Aqueronte72

8

|

jun. 16, 2025

The confusion is evident in Piera. She began to question whether having everything meant that nothing was missing. But that is precisely the crux of this approach, which, mind you, did not point—although it did not rule it out, as we shall see in the plot—towards lesbianism, but rather towards the emotional or existential incompleteness that canonical institutions such as marriage offer couples at the dawn of the Generation X era.

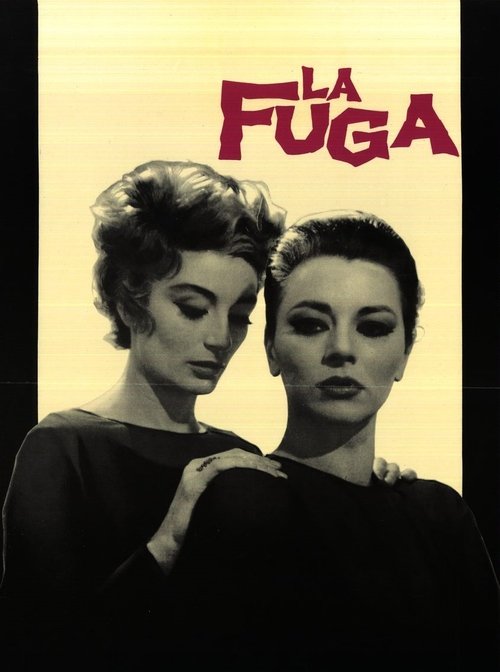

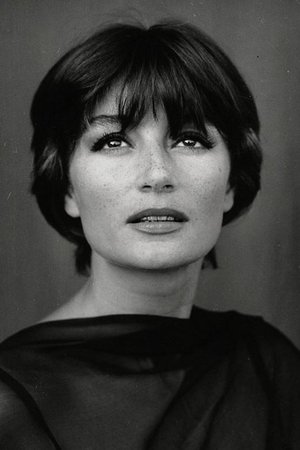

At first glance, it seems like a nod to the same kind of ennui—as a substitute for existential weariness in crescendo—found in ‘La Notte.’ I’m not just referring to the minimalist staging, which is most noticeable in its use of luminous actresses of the time, such as Anouk Aimée and Ralli, or the striking parallels between the two films, both in the contrasting cinematographic framing and in the effective piano soundtrack performed here by Piccioni, but also in the essence of the latent indifference between Andrea and Piera. But Antonioni did not invent the theme of the lack of communication that springs precisely from the invisible cracks in the marital or emotional stability between a woman and a man who are supposed to love each other. As I said at the beginning, Piera is not fulfilled by motherhood – she even feels that she is not a good mother to Vittorio; she is not fulfilled by her life with Andrea at the nuclear plant; she is not fulfilled by the days of leisure at her mother’s villa in Porto Ercole, nor is she even satisfied by having her own time – which seemed to be a luxury for a woman even in the 1960s – for her art, which unintentionally attracted Luisa’s attention, even if only as a pretext. ‘Andrea says that a woman should only think about the house and the children,’ she tells her mother when she tells her about Luisa’s offer to work with her.

That’s what she needs, to free herself from the yoke inherited from the Baby Boomer generation, at least from the interwar period. She confesses that she envies Luisa, her loneliness and time alone. Meanwhile, Piera continues to dream of trains and alienating walks that curiously convey her subconscious, which is why she goes to a psychologist who seems to be thinking about her, as she suspects.

We see Aimée’s character profile and we see her, Piera, and it’s as if Coco Chanel had set her sights on a bourgeois housewife to vent her adventures and unleash her power drives, and Piera is like a woman who is clearly neglected in her femininity and realises that she can attract a woman with trousers and art and walks in Cala Piccola, with whom she actually runs away. If I rated it 8/10, it’s not because I think this work is as sublime as Antonioni’s, but it’s quite interesting for its time anyway; I rated it that way because this work has its own charm in a vitalistic subtext that resonated less and less subliminally and abstractly at the time. In this regard, I love that the narrative thread here is monologued, as if it were Piera’s epistolary to herself.

This style, together with the superb photographic pans, has caused me very pleasant emotional outbursts, for example when she narrates the unexpected arrival of Luisa the sanado and how, not knowing Argentario, they decided to visit him together with Vincenzzo. This whole passage seems to be shot with aspects and cameos that convey a dreamlike atmosphere while she narrates and the piano is heard. Was the image shot in the early hours of the morning, minutes before dawn, or, on the contrary, at dusk? Honestly, I think it ruins the avant-garde approach to justify the film with a flashback to before they got married, starting with the visit to the psychoanalyst in the second part of the film. Obviously, the divorce would have to come from Andrea, using their son as an excuse for the sexist attitude that was common in the 1950s and earlier regarding women having permission to work while neglecting their children, while she aspired to more. In any case, the outcome could not be less discouraging for Piera than she could have imagined.

Divorced, going to Luisa’s company, that afternoon when some young men called the hotel room where Luisa and Piera were staying, inviting them to Ravello, Luisa refuses and Piera recalls this with the psychoanalyst: ‘She was there. Waiting for me to offer myself. And I didn’t have the courage. But inside me I wanted her desperately’. Everything vanished after she never saw her again, like a ghost. The ending seems unnecessary, because at first glance it seems to offer a useless epilogue summarising the film in the dialogue between Andrea and the psychoanalyst regarding the certainty of the energy of matter, in comparison with human feelings. Then the psychoanalyst replies, ‘Luisa Crevelli? I don’t think I’ve ever heard that name,’ responding to Andrea’s question about whether, in his professional opinion, she was the cause of his divorce. Was it all just a figment of the male imagination? Or, better yet, were there romantic intentions but he never revealed them to the doctor?