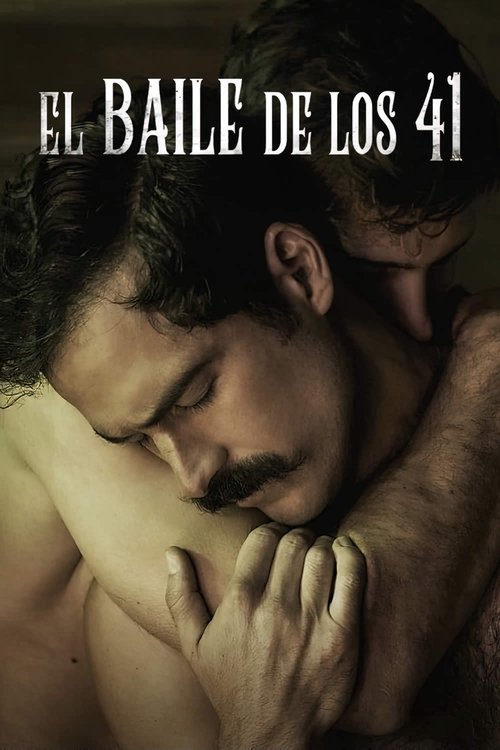

Danybur

9

|

may. 15, 2021

“Algunos deberes cuestan más que otros”

Sumario

Notable abordaje de un escándalo social, político y sexual ocurrido en México en 1901. La apuesta por el melodrama concentrando la acción en un triángulo amoroso es un gran acierto del guion, sin perder de vista la descripción precisa y lograda del club clandestino de homosexuales al que concurría el protagonista, diferenciándose de tanto producto hollywoodense “basado en hechos reales” que apuesta a abarcarlo todo abrumando con información.

El director David Pablos realiza una puesta en escena deslumbrante y los diálogos y las actuaciones son de primera en una película de ecos viscontianos y que confirma una vez más a los mexicanos como los maestros indiscutidos del melodrama.

Un testimonio del homoodio de entonces (que no se detenía ante privilegios de clase) y que sigue teniendo renovados ecos en el presente que están lejos de acallarse, particularmente en países como México y tantos otros.

Reseña

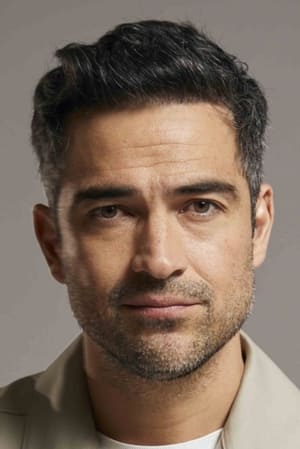

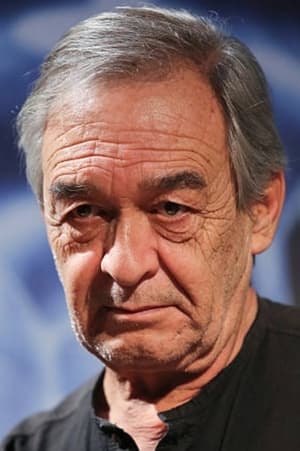

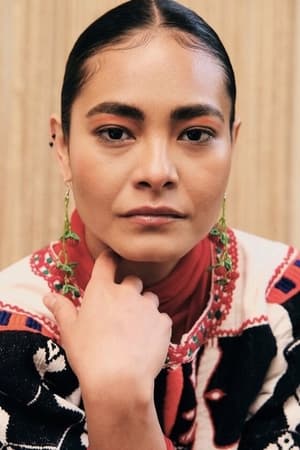

La película comienza con la fastuosa fiesta de compromiso del ambicioso diputado Ignacio de la Torre (Ignacio Herrera) con Amada, la hija del presidente mexicano Porfirio Díaz (Mabel Cadena) ahí por el año 1900. Lo que nadie sabe aún es que Ignacio es un homosexual tapado que concurre a una suerte de club clandestino de homosexuales y que terminará vinculándose con Evaristo Rivas (Emiliano Zurita), un empleado del Congreso.

Este notable film de David Pablos reúne un cúmulo de aciertos. Primero porque apuesta al melodrama para abordar un escandaloso suceso histórico ocurrido en 1901 en Ciudad de México y que nadie se había atrevido a abordar, concentrando la trama en el triángulo amoroso que constituyen Torres, Amada (una verdadera ironía que se llamase así) y Rivas, con sus progresivas y complementarias historias de amor y desamor. Sin embargo, las escenas que transcurren en el club son harto suficientes para describir el perfil de sus miembros, sus códigos, sus dinámicas y las actividades que se desarrollaban ahí. Por otro lado, el contexto sociopolítico queda muy claramente expuesto y sin subrayados molestos. Este enfoque marca una enorme diferencia con los productos hollywoodenses “basados en hechos reales” que saturan de información en su pretensión de abarcarlo todo, lo que lleva a desarrollos esquemáticos de sus personajes.

El guion de Monika Revilla (no casualmente también guionista de Alguien tiene que morir) es sumamente preciso, en una historia donde los personajes hablan sólo lo necesario.

La puesta en escena es deslumbrante: la ambientación y el vestuario nos ubican convenientemente en el extracto social alto de los personajes, la fotografía es una maravilla y el director logra un cúmulo de efectivos, expresivos y virtuosos planos secuencia que acompañan, cuando es necesario, a sus personajes y variando el registro según la escena que describe. Como en todo buen melodrama, no faltan la ironía y cierto humor amargo, como ocurre en una antológica escena en que Amada toca el piano.

Las actuaciones de los protagonistas son muy buenas, en personajes que presentan varios matices dentro de sus perfiles bien definidos en una historia que es una verdadera olla a presión.

El baile de los 41 es un testimonio, por un lado, de cómo ni siquiera el dinero y los privilegios podían poner una vida sexual libre y privada absolutamente a resguardo de la homofobia, el homoodio y el escarnio del establishment político, religioso y social del México (y del mundo) de entonces y que sigue teniendo renovados ecos en el presente que están lejos de acallarse, particularmente en países como México.

"Some duties cost more than others"

Summary

Remarkable approach to a social, political and sexual scandal that occurred in Mexico in 1901. The bet on melodrama concentrating the action in a love triangle is a great success of the script, without losing sight of the precise and successful description of the clandestine homosexual club at the that the protagonist concurred, differentiating himself from so much Hollywood product "based on real events" that he bets to cover everything overwhelming with information.

Director David Pablos puts on a dazzling staging and the dialogues and performances are first-rate in a film with Viscontian echoes that once again confirms Mexicans as the undisputed masters of melodrama.

A testimony of the homoodium of that time (which did not stop at class privileges) and which continues to have renewed echoes in the present that are far from being silenced, particularly in countries like Mexico and many others.

Review

The film begins with the lavish engagement party of the ambitious deputy Ignacio de la Torre (Ignacio Herrera) with Amada, the daughter of Mexican president Porfirio Díaz (Mabel Cadena) back in 1900. What nobody knows yet is that Ignacio is a A covered homosexual who attends a kind of clandestine gay club and ends up linking up with Evaristo Rivas (Emiliano Zurita), an employee of Congress.

This remarkable film by David Pablos brings together a host of successes. First, because it bets on melodrama to address a scandalous historical event that occurred in 1901 in Mexico City and that no one had dared to address, concentrating the plot on the love triangle that Torres, Amada (a true irony that was called that) and Rivas constitute. , with its progressive and complementary stories of love and heartbreak. However, the scenes that take place in the club are enough to describe the profile of its members, their codes, their dynamics and the activities that took place there. On the other hand, the socio-political context is very clearly exposed and without annoying underlining. This approach marks a huge difference from Hollywood "fact-based" products that are information-saturated in their all-encompassing claim that produces schematic developments of their characters.

Monika Revilla's script (not coincidentally also the scriptwriter of Someone has to die) is extremely precise, in a story where the characters speak only what is necessary.

The staging is dazzling: the setting and the costumes conveniently place us in the high social extract of the characters, the photography is wonderful and the director achieves an accumulation of effective, expressive and virtuous sequences that accompany, when necessary, to their characters. As in all good melodrama, irony and a certain bitter humor are not lacking, as in an anthological scene in which Amada plays the piano.

The performances of the protagonists are very good, in characters that present various nuances within their well-defined profiles in a story that is a true pressure cooker.

Dance of the 41 is a testimony, on the one hand, of how not even money and privileges could put a free and private sex life absolutely safe from homophobia, homo-hate and the derision of the political, religious and social establishment of the Mexico (and the world) of then and that continues to have renewed echoes in the present that are far from being silenced, particularly in countries like Mexico.